Sustain / Real Bread Campaign / Articles

Hole lotta love

The beigel isn't just a roll with a hole, says Francesca Baker.

Head to the baked goods aisle of any supermarket and you will find sliced loaves, rolls, flatbread, farmhouse bloomer, cob, ciabatta, naan, focaccia, brioche, baguette, and more. Amongst these will be wraps, pittas and beigels that, according to a Mintel report, together make up 43% of the UK ‘bread’ market.

But are they all really just the same dough just shaped differently? Well, they shouldn’t be. The beigel has a cultural, historical and epicurean history that has been moulded and changed as its popularity has increased

Ring ring

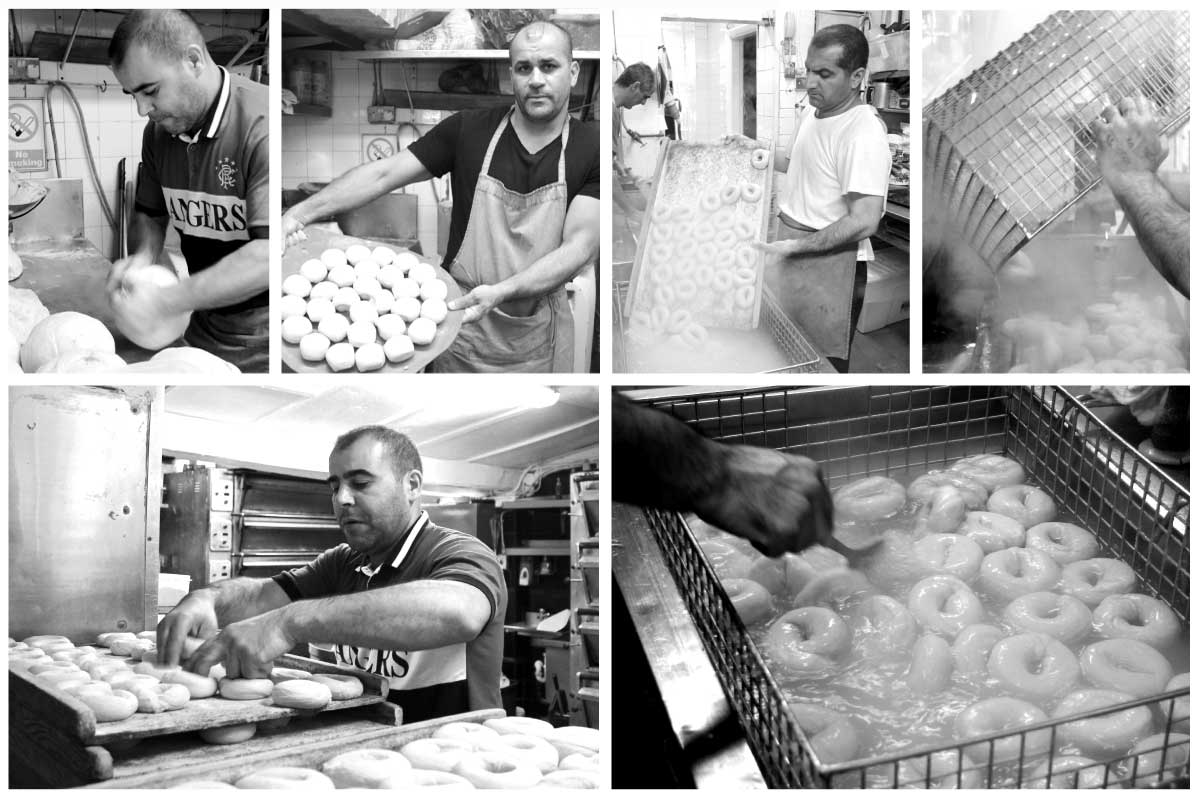

The recipe and process is simple. A tight, white wheat flour, yeasted dough is shaped into a ring, proved and then boiled briefly before baking.

Perhaps the first known written record of the word beigel is in the 1610 community regulations of Krakow, which noted that they were baked as gifts for women in childbirth. Various theories as to the formation of the name exist, but the common theme seems to be that its roots lie an old European word for ring.

Origins

The history of the beigel is intertwined with that of eastern European Jews and one theory for the boiling is that Halakha (Jewish law) dictates that cooking is not permitted on the Sabbath period. Beigel dough was therefore mixed and shaped on a Friday afternoon, left in a cold place over the Saturday and then once the Sabbath was over immersed in boiling water to re-activate the yeast ready for the morning meal.

Whether or not this is true is debatable. Maybe boiling was in fact done on the Friday evening for long enough to stop the yeast working, leaving the beigel ready to bake straight away when needed – a predecessor to the modern bake-off process, perhaps? Whatever the reason, the boiling gelatinises the outside of the dough, restricting its expansion during baking, resulting in dense, chewy texture and a glossy, smooth crust.

Crossing the pond

Taken to northern America by Polish and other east European Jews in successive waves from the late 19th Century, the beigel found new homes in there in larger cities. But there are differences. For example, the New York beigel contains salt and malt and is, after being boiled in plain water, baked in a standard oven. Meanwhile the Montreal beigel has no salt, is boiled in honey-sweetened water and baked in a wood-fired oven.

British beigels

Having being opened by the Lieberman family around sixty years ago and run by its current owners since 1976, Beigel Bake on Brick Lane in London has become something of an institution. “There was those ladies who sold the bagels who could curse so nicely people came to hear the curses,” Rachel Lichtenstein quotes one former resident’s post-war recollections in her book On Brick Lane.

Mister Sammy and his team have been using the same recipe for nearly forty years and the question as to how they make their infamous products was met with near derision. “We boil and bake our beigels, how else would we?” It certainly goes down well. They make around 7,000 a day and the 24 hour establishment has queues stretching outside at all times of day throughout the year.

When is a bagel not a beigel?

Increasing demand and promise of gelt (money) has led some industrial bakers into mass production and the humble beigel has been bastardised. The process of shaping and boiling each one is considered too labour intensive, and so many commercial bakeries use a steam-injected oven. It might look the same, but it’s not – as doesn’t taste as good.

Today over five million longer-life products marketed as bagels are sold per year in America and millions more around the world. Chain stores sell them, brands package them and amongst the numerous adaptations are cinnamon, gluten free, wholemeal, cheese and more. According to a baker at Roni’s in north west London, however, such products can’t be considered the real thing as an “authentic beigel can’t have a shelf life of more than eighteen hours.”

So, when you are next chomping away on your holey treat, remember that it’s the process that counts. Making something with love, using natural ingredients and an authentic recipe will always result in better food.

Ode to a Beigel

In the words of poet Wally Glickman:

Blessed bread with chewy soul,

Serene, yet joyous, noble, droll,

Who leads in each Semitic poll,

On porcelain plate, on beggar’s bowl.

In luncheonette, on grassy knoll.

No baguette, brioche or roll

Can dare compare with thy sweet hole.

Originally published in True Loaf magazine issue 25, October 2015.

Published Wednesday 15 January 2020

Real Bread Campaign: Finding and sharing ways to make bread better for us, our communities and planet.